Where is the Basilica of St. John at Ephesus?

The Basilica of St. John at Ephesus is situated on the slope of Ayasuluk Hill in Selcuk, Ephesus, Turkey, within easy reach of the Ephesus archaeological zone. From here, you can see the nearby Isa Bey Mosque, the remains of the Temple of Artemis down on the plain, and the rugged profile of Ayasuluk Castle watching over everything.

ℹ️ 2026 Visitor Information

- 📍 Location: Ayasuluk Hill, Selçuk Center.

- 💰 Entrance Fee: 6 Euros per person. Museum Pass is Valid.

- ⏰ Opening Hours: 08:00 – 19:00 (Summer), 08:00 – 17:30 (Winter). Open every day.

- 🚶 Accessibility: It involves some uphill walking and steps. Not fully wheelchair accessible.

- 💡 Pro Tip: Visit late in the afternoon for the best sunset view over the Temple of Artemis.

Table of contents

- Where is the Basilica of St. John at Ephesus?

- 🗺️ Interactive Map: Walk Through the Holy Site

- Significance of the Basilica of St. John

- The Evolution of the Basilica of St. John

- The Tomb of St. John

- Architectural Significance and Details

- Sacred Spaces: Tomb, Baptistery, and the Church “Treasury”

- Early Christianity in Ephesus

- St. John’s Journey to Ephesus and Legacy

- How to get to the Basilica of St. John at Ephesus?

- Featured Biblical Ephesus Tours

- Frequently Asked Questions about St John in Ephesus

- You May Also Like

✝️ Top 5 Sacred Highlights to See

Don’t wander aimlessly among the ruins. Find these holy spots:

- ⚰️ The Tomb of St. John: Located exactly under the central dome. The heart of the Basilica.

- ⛲ The Baptistery: A key area for early Christians used for full-immersion baptism.

- 🗝️ The Treasury: A secure stone room that once held the church’s gold and relics.

- 🏰 The View of Ayasuluk Castle: The best panoramic photo spot looking up at the fortress.

- 🏛️ Justinian’s Monograms: Look closely at the column capitals to see the Emperor’s signature.

🗺️ Interactive Map: Walk Through the Holy Site

Follow this route to experience the Basilica from the entrance to the sacred tomb.

1. The Atrium & Narthex

Enter through the “Gate of Persecution.” This open courtyard was where pilgrims gathered before entering the sacred space. Look for the ancient columns reused from the Temple of Artemis.

📸 See Details2. The Tomb of St. John (The Core)

This is why you are here. Beneath the central dome lies the burial place of the Apostle John. The platform is raised, marked by four columns. This spot has been a pilgrimage center for 1500+ years.

📸 See The Tomb3. The Baptistery

Located to the north of the nave. You will see a keyhole-shaped pool used for full-immersion baptisms in the early Christian era.

📸 See Details4. The Treasury & Chapel

A secure stone room adjacent to the main church, used to store sacred vessels and gifts from wealthy pilgrims.

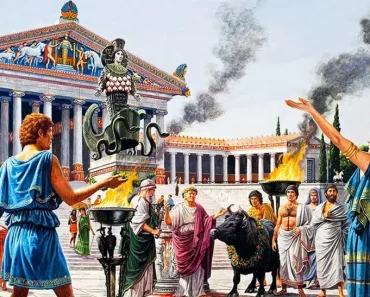

📸 See DetailsSignificance of the Basilica of St. John

The Basilica of St. John was built in the 6th century by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I over what tradition holds to be the tomb of John the Evangelist. It is believed that the Apostle John resided in Ephesus after being exiled to the Isle of Patmos. He died here at the age of 98 and was buried in the exact location according to his will. The Basilica is believed to be the final resting place of John the Apostle and was constructed over what is considered the tomb of St. John.

Who Was St. John the Evangelist?

Apostle, author, and exile

Traditionally considered the youngest of the Twelve Apostles, St. John is credited with authoring the Gospel of John, three Epistles, and the Book of Revelation. The early Christian tradition states that he ministered in Ephesus, was exiled to Patmos under the Roman Emperor Domitian, and later returned to spend his final years in Ephesus.

John’s connection to Ephesus and Patmos

Patmos is where Revelation is said to have been written; Ephesus is where John taught communities and where his tomb became a place of devotion. The vision of a double footprint on an island and ministry in a metropolis explains why this basilica has attracted pilgrims for centuries.

The Basilica of St. John at Ephesus Video Guide

The Evolution of the Basilica of St. John

Early Christian shrine over the tomb

Long before domes dominated the skyline, a humble memorial and a small church likely marked the venerated tomb. Pilgrims visited to pray at the site, and its fame grew as the Roman Empire Christianized.

Early Foundations and Theodosian Church

The first building was a Martyrion (Mausoleum) built on the grave of St. John, which was also used as a church. In the era of Emperor Theodosius (347-395), a basilica was built over the mausoleum. Two hundred years later, the building became nothing more than a wreck due to earthquakes.

Theodosius to Justinian: Architectural Evolution

In the mid-500s, Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora initiated an ambitious building campaign throughout the empire. Alongside the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the emperor commissioned a monumental basilica here in Ephesus to honor John the Apostle. The plan was not modest: a cruciform basilica with multiple domes, soaring arcades, and richly adorned interiors. And eventually, above the church of Theodosius, a massive church with a cross plan was built by Emperor Justinian and his wife Theodora (548-565). The building of this basilica, modeled after the lost Church of the Holly Apostles in Constantinople, had a cross plan with six domes. And the sacred burial place of St. John was under the central dome.

The Tomb of St. John

In the Middle Ages, pilgrims believed that a sweet-smelling dust, called “Manna,” rose from St. John’s tomb on his feast day (May 8th). This dust was collected and used for healing sicknesses throughout Christendom. While the miracle is a legend today, the spiritual atmosphere remains.

The Crypt and the Tradition Around it

Beneath the crossing lies the revered spot traditionally identified as John’s burial. In Late Antiquity, pilgrims described a dust or fine ash said to rise from the tomb on certain days, believed to have healing power. Whether or not you accept the tale, standing above the site connects you to over a millennium of devotion.

Pilgrimage, Dust Relics, and Devotion

Medieval pilgrims cherished small reliquaries of soil or dust from holy tombs. The basilica’s guardians regulated access, directing believers along defined paths. This movement approach, which venerates, departs, made the church itself a narrative of hope and healing.

Architectural Significance and Details

Massive marble pillars in the corners of the cross support five domes. On the capitals of the pillars, the monogram of Justinian and Theodora was placed, before Theodora died in 548. The main entrance gate to the church was called the “Gate of Persecution,” and a large baptistery was located to the left of the Gate of Persecution. The massive Basilica of St. John at Ephesus, measuring 133 meters in length and 65 meters in width, was regarded as one of the holiest churches of its time.

Cross-shaped Plan and Domes

The church was designed in a Latin-cross plan, with a long main section and a wide cross section that creates arms around the center. Experts believe there were up to six domes along the main axis, with the largest dome over the intersection. Even in its ruined state, the church’s structure is still visible through the foundation walls, column bases, and spaced piers.

Narthex, Nave, Aisles, and Transept

You would have entered through a narthex (a porch-like entrance) into the nave. Side galleries flanked the central hall, guiding processions toward the crossing and apse. The transept arms acted like open wings, expanding the space for feasts and central liturgy. The hierarchy of spaces, threshold to heart, was a theological choreography in stone.

Materials, Spolia, and Craftsmanship

The builders used brick and stone together, sometimes reusing (“spolia”) fine Roman and Late Antique pieces, columns, capitals, and marble slabs. You’ll spot distinctive impost capitals and fragments with vine scrolls or crosses peeking from the grass. Floors likely featured a combination of marble paving with sections of opus sectile (cut-stone inlay), a luxury finish that caught candlelight like water.

Sacred Spaces: Tomb, Baptistery, and the Church “Treasury”

Not all ruins feel sacred, but this one often does. The tomb platform lies beneath a simple dome with a cut-out in the marble marking the burial site. To the north, the baptistery, dated to the 4th century by some, reflects a community growing through ritual initiation. Within the complex, a room known as the treasury likely stored offerings and valuables, addressing the risks of life in timber-rich towns, like fires and theft. Together, these spaces convey a powerful story: memories draw people, rituals shape experiences, gifts sustain the shrine, and architecture allows for organized devotion.

The Tomb at the Crossing

Every route leads to this site. Under the central dome, once supported by four corner piers, rests the tomb of John, slightly raised and edged in marble. The remarkable geometry serves as a spiritual and physical center, with sightlines from each arm of the cross converging on the grave. Pilgrims would line the aisles (Halls) to pray, touch the tomb, and collect dust for their journeys. The modern presentation keeps the platform open and visible, allowing visitors to appreciate the layout that frames each encounter. Its simplicity suits an apostle known for a Gospel of clarity.

The Baptistery and the Ritual Life of the Church

Baptismal spaces in Late Antique churches weren’t afterthoughts; they were the front door into the community. At St. John’s, a baptistry dated by local signage to the 4th century survives in part, reminding us that this hill wasn’t just a memorial; it was a working parish with feasts, fasts, and catechumens learning the creed. Picture the steps: learning about the faith before Easter, participating in a nighttime vigil, being baptized in water, and receiving the first Eucharist in the basilica.

A Medieval “Safe Deposit”? The Treasury and Offerings

Travel writers love the detail that one room functioned like a medieval safe deposit box, where parishioners stored valuables in safer stone quarters rather than in wooden houses prone to fire. Whether you buy the analogy or not, the logic fits the economics of pilgrimage sites, which handled offerings, liturgical vessels, and sometimes community funds. It’s a reminder that sacred places are also organizations with budgets and back rooms.

Early Christianity in Ephesus

Ephesus served as a critical hub for early Christianity, a fact underlined by the Apostle Paul’s letters and the city’s mention in the Book of Revelation. The basilica’s construction in this historical and spiritual context highlights its significance as a beacon of faith.

St. John’s Journey to Ephesus and Legacy

There were no clear written inscriptions about the travel of St. John to Ephesus. However, it is believed that John traveled from Jerusalem to Ephesus, where he remained for the rest of his life after the crucifixion. Numerous evidence confirm John’s residence in Ephesus, and from there Emperor Domitian exiled him to the Isle of Patmos for 8 years, where he wrote Revelation (the Apocalypse). During the time of Emperor Nevra, John was forgiven and returned to Ephesus, where he spent the rest of his life.

St. John was the youngest of the apostles and is said to have lived to old age, dying at Ephesus (A.D. 93-94) during the reign of Emperor Trajan. It is believed to be the same person as John the Apostle (John, son of Zebedee), and the author of the Gospel of John.

The most critical document confirming St. John’s residency in Ephesus is the letter from the Ecumenical Council held in Ephesus (A.D. 431). This letter describes “the city of Ephesus” as where John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary lived and were buried.

Siege, Earthquake, and Change

Medieval Damage and Repairs

Time was not gentle. Earthquakes, periodic raids, and the shifting fortunes of the region led to collapses and partial rebuilds. As political centers moved, maintenance waned. Roofs failed; rain and plants took their slow tax.

Seljuk Era, Ayasuluk Castle, and the Reuse of Stone

During the Seljuk period, Ayasuluk Hill remained strategically important. Builders reused fine marble from the basilica in new works, most famously in the 14th-century Isa Bey Mosque, located just downhill. This wasn’t vandalism; it was the medieval way: cities evolved by weaving old stone into new stories.

Theology, Myths & Misconceptions

Did St. John die in Ephesus?

Tradition, supported by early church writers, places John’s last years in Ephesus and his burial here. Exact dates vary in ancient sources; rather than pinning it to a modern calendar, it’s more faithful to say: Ephesus holds the memory of John in a way few places can.

Did he write Revelation here or on Patmos?

The Book of Revelation is associated with John’s exile on the island of Patmos; the Gospel and letters are connected to the Ephesian community. Rather than competing claims, think of them as two halves of one larger ministry.

How to get to the Basilica of St. John at Ephesus?

- From Selcuk Center: It’s a brief uphill walk (1-2 km) or a quick taxi ride to Ayasuluk Hill.

- From Ephesus Ancient City: The basilica is located approximately 3–4 km from the lower gates of the Ancient City of Ephesus.

- From Kusadasi (Cruise Port): Roughly 20 km, about 25–30 minutes by road.

- From Izmir Adnan Menderes Airport (ADB): About 60–70 km; plan roughly 1 hour by car.

- From Izmir city center: About 80–85 km; allow 1.5 hours by car or take the IZBAN train to Selcuk and taxi/walk up the hill.

Featured Biblical Ephesus Tours

Frequently Asked Questions about St John in Ephesus

Ephesus remains a city situated within the borders of İzmir, Turkey, today. The current name of Ephesus is Selcuk. The Selçuk district of İzmir, which is today’s Ephesus, has a population of approximately 36,000.

Although we do not have any written inscriptions, there is a strong belief that St. John came to Ephesus with the Virgin Mary after Jesus was crucified. However, there is much evidence confirming that Emperor Domitian exiled St. John to the Isle of Patmos for 8 years. During the reign of Emperor Nevra, John was pardoned and returned to Ephesus, where he spent the rest of his life.

Today, the ancient city of Ephesus, which dates back to the Hellenistic and Roman periods, continues to draw millions of tourists. In addition, life in modern Ephesus continues as a district of Izmir, now known as Selcuk.

The distance between Ephesus and Jerusalem is approximately 10,500 kilometers.

Right after Jesus was crucified, St. John immediately set out for Ephesus to spread Christianity and protect the Virgin Mary.

According to belief, St. John spent his last days in Ephesus, and his tomb is located in the Basilica of St. John in Ephesus today.

The basilica was built directly over the traditional tomb. The crypt area beneath the crossing marks the venerated spot.

According to tradition and historical accounts, when the tomb was opened by Emperor Constantine’s order (or later archaeologists), no body was found inside, only dust. This led to the legend of the “Manna” (sacred dust) that was believed to have healing powers in the Middle Ages.

You May Also Like

If you would like to explore the Basilica of St. John in Ephesus with us on-site, please reach out using the links below.